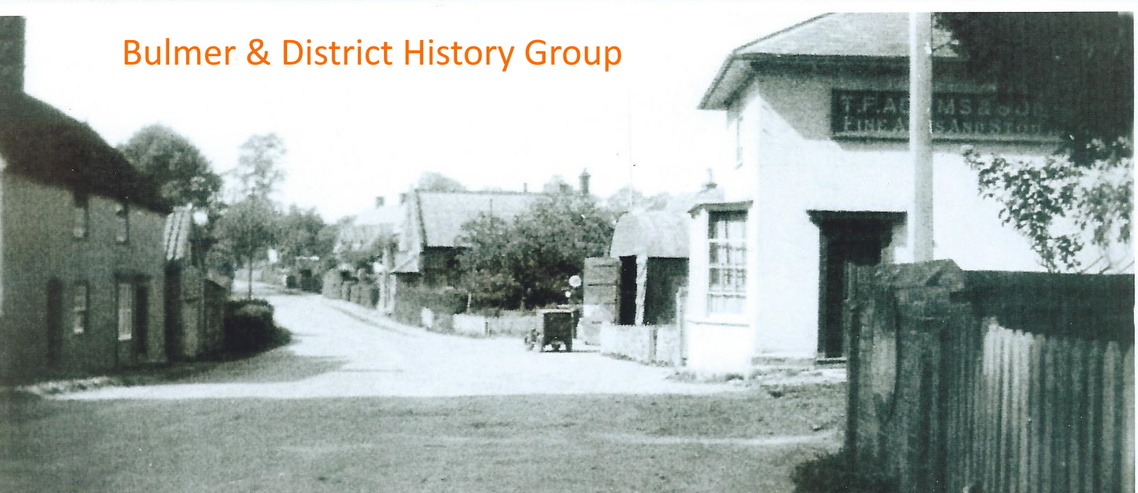

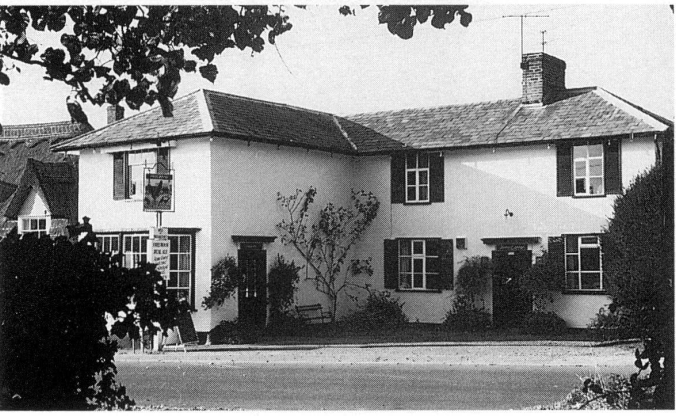

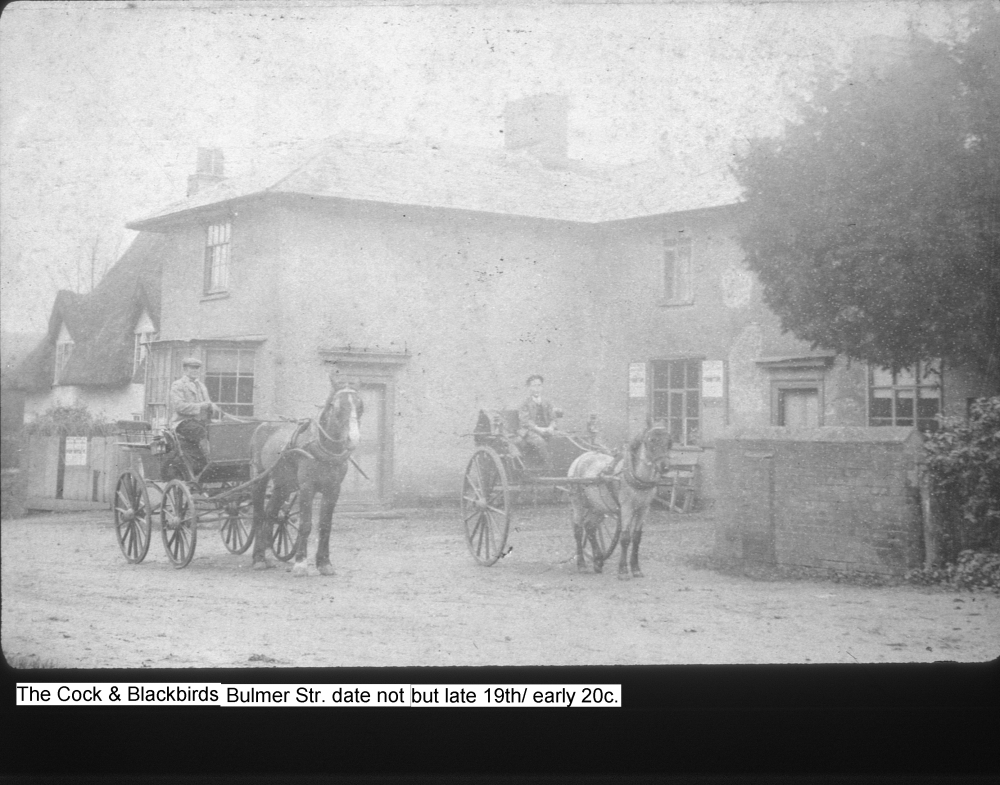

The Bulmer `Cock and Blackbirds'. The legendary `tap room' was on the right. The pub's famous weather-vane — a metal cockerel also remains. During World War Two a hole was shot through the tail.

An early reference to the Cock and Blackbirds comes from the Essex Register of Licences, which records the pub’s existence in 1769. Another pub—in addition to the Cock—was opened in 1783, when John Brue registered the Plough, (which was situated on the Tye, close to the turnpiked road.) By 1882, the Plough was no longer registered. Also on the Tye, was the Bulmer Fox which had existed since at least 1863. Another pub, just beyond the Tye on the road to Halstead was The Greyhound, which relinquished its licence in 1907. (It stood beside the main road and the junction with Watery Lane,)

Threshing contractor and smallholder Jack Cornell, (b.1918), was brought up at the Bulmer `Cock and Blackbirds', where his father, John was the landlord from 1920-1936. Jack’s vivid, enthusiastic memories of his boyhood, village cricket and rural life did much to inspire this book. Let us imagine it is the early 1930’s……

"I remember one time in the Blackbirds. This pompous old farmer came stumping in and chancing to see his shepherd said, smarmy-like `What'll you have then? Beer? Whisky?' You can guess the reply can't you. `Huh,' say the old shepherd. `Seeing as it is you then... Both!"

After leaving Bulmer, Jack moved to a small-holding at Little Maplestead. It was here, just after 8.30 one February evening that my investigation continued.

"Father took the Blackbirds in 1920. Course, the layout was different then; so for that matter was the type of mugs that they drank from. When Father started they were all pottery mugs — platter mugs I think they called them — trouble was that when you were serving you couldn't see when the damn things were full! In fact I can clearly remember my father buying the glasses — and all the old men saying that the beer didn't taste right!

"Did you do any food?"

"Not really. Mother might make up a bit of cheese and pickles if someone specially wanted something, but it wasn't a regular thing like today. You see food was perishable in those days and you couldn't keep a supply on the `off chance'. There were occasional dinners though. Lacy Scott, the estate agents, who managed Belchamp Hall, used to give one for the farmworkers instead of a horkey; and there might also have been one for the Football Club. But there wasn't a lot of it done. Still, I expect it brought in a few more shillings."

"At least in your Father's day," I said knowingly, "there was enough local trade to make a village pub pay." "Tain't so likely!" came Jack's swift retort.

"Really?" I replied — slipping another cassette into my tape recorder.

"I mean, there might have been in the towns and beside the main roads, but no; a village pub has never been a full time living. I'll tell you this. When Dad kept the Blackbirds, he would go biking off to his threshing tackle at six o'clock in the morning, do a full days work and then keep the pub until 10 o'clock at night. No, there was nothing in a pub if you didn't enjoy doing it. I reckon he just about got enough to pay his rent and rates and perhaps a bob or two on top — but not a great sight more. He'd have been a long while getting very rich without the threshing!"

"And most other small village pubs were the same?"

"Oh yes. Some publicans ran brickyards; others did blacksmithing — one or two of `em might have had a windmill' and a lot of `em would do an odd days threshing or something of that sort. Tom Mansfield at the Otten Windmill was a regular helper when we worked over there."

"In the last twenty years, " I commented seriously, "the Belchamp, Gestingthorpe and Bulmer pubs have all changed hands about once every six years. Was it the same when you were young?"

"No. People used to stay in pubs for years and years and often keep it in a family for generations. Things were different in those days; it really was something to have a good roof over your head and most of the `brewery houses' were well kept up."

"But you had a good regular trade in those days?"

"I don't think it was much different from now. In the winter a village pub would be almost deserted on weekday nights. Apart from a couple or three in the `tap room' there was hardly any trade at all. Course, Friday and Saturday nights were much more lively".

Observing that there seemed to have been more different rooms in a pub years ago, (at the Blackbirds there was a `tap' room, public bar, smoking room and club room or lounge), Jack provided the following explanation — as the hands of his mantelpiece clock touched 10.15.

"What was the `tap room'?"

"IT WAS THE BEST PLACE IN THE WHOLE BLOOMIN' PUB! Least that's where we had the most fun. If you were coming home straight from work, it is where you could go, without taking off all of your `clobber' and hob-nailed boots. It was only a small room with a wooden floor and wooden forms along the sides where you could sit."

The sparse furnishings led to an amusing memory: "Makes you laugh to think of it though, but on a Sunday night in the tap room, Uncle Harry Rowe would cut some 'bacca' up with a shut knife and there would be him and two or three old men with these `ere clay pipes on the go! Well, talk about the smoke! It was enough to cackle you! You could hardly see from one side to the other. God alive!! You didn't ever need to fumigate it!"

On one occasion, a customer came in with an unusual item….

"One night when we boys were all in the Blackbirds, this old man came stumping in with a bucket which had an old sack on top of it. "Just caught a swarm of bees," he said, pointing to the bucket.

Anyway, he drew up a chair and put the bucket beneath it. "Well, all us lads kept looking at this bucket. Then the old man rose up and leant towards the fire to light a piece of paper for his fag. In a flash, someone had half-pulled his chair away. He almost sat in the bucket! Course, no harm was done, but just think of that — taking a bucket full of bees into a pub!"

‘What about the beer—and the barrels it came in?’ I wondered.

"Talk of a struggle," laughs Jack, as I stand in the door of his kitchen `well after midnight'. "At the Blackbirds we had to push those eighteen gallon barrels UP a five foot ladder from the cellar and then over six or seven steps to the bar. They must have weighed at least 1801b (80kg)... well, you jolly well wanted a pint or two time you'd done that sort of work!"

"What about la... " I was just about to ask.

"What about what?"

"Lager?" I suggested contritely.

"Never been heard of Not that time of day. And precious few shorts were ever drunk because no-one could ever afford them."

"Like a good landlord," quips Jack. " 'Course," he continues, "pubs used to shut at ten when I was a lad and it wasn't a bit unusual for the village policeman to come and sit on his bicycle outside and start pulling his watch out. And that was it! You had to be moving! 'Course I remember one time... "

It is almost two o'clock. Jack is telling me of the Blackbirds and of an evening after harvest when he was still a boy. "It hadn't been a proper horkey — not in the traditional way, but they had an almighty good booze up!

"Anyway, the old copper came at ten o'clock and everyone had to leave. But poor old `George' was pretty much the worse for wear. He swayed out singing and laughing and then staggered up the avenue to Bulmer Church. Well, the of bobby was good enough to follow him at a distance.

Anyway, George kept hollering and lurching about and just about made his way up to the graveyard. But that was it. He just couldn't go a step further. He just collapsed —there and then — and laid down amongst all the graves and tomb stones. So, the policeman walked up and shook him on the shoulder. `Come on,' he said, `you can't lay here all night.'

`Who says?'

`I do.'

"George just raised himself on one shoulder — and very weakly pointed to the gravestones. `Tell some of them other buggers to move,' he said. `... they've been here long enough!

**********************

"If people got cut by something sharp," recalled Jack's sister Evelyn on a different occasion, "they would smear grease onto the object that had cut them... even BEFORE getting bandaged up. When we kept The Blackbirds, a man came in and asked Mother for some grease because he had cut himself on a nail — and he wanted to grease it!"