Most early schoolrooms were built with donations from wealthy parishioners. At Bulmer it was Squire Alexander of The Auberies who financed the rebuilding of 1840, (considerably extended by J. St. George Burke in 1874).

At Bulmer School, says Jack Cornell, "the slates had squares on one side and three lines on the other." However, when he 'went up into the big room' Jack graduated to dip in pens and ink wells. Writing had to be 'thin up and thick down'. But stop! Look! The poor lad next to Jack has suddenly got a dry inkwell. Surely some mischievous neighbour hasn't dried it out with blotting paper?

Possibly, like so many others, the sneaking suspicion may have crossed his mind that 'school wasn't such a bad place after all'. Girls sometimes stayed on. Another Bulmer pupil, Emily Hearn (1890-1983):

"did about six months helping to teach the small children - as a 'monitor' - before I went into service. "Meanwhile the boys of Bulmer School who, 'always had to touch our hats if ever we saw the schoolmistress walking round the village - now adamantly refused to do so.' Maybe the offended teacher hissed in return: 'civility costs you nothing, Cornell!' "It was one of her favourite expressions," recalls Jack. ''I've often thought about it since."

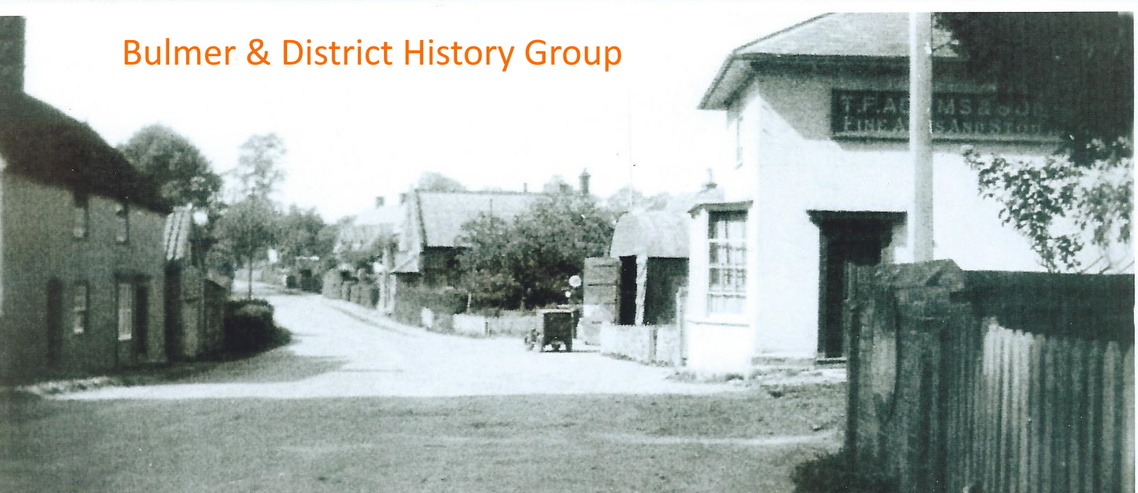

Bulmer schoolteacher Basil Slaughter and historian Arthur Brown sowed the seeds of this book at W.E.A. lectures held in Bulmer and Gestingthorpe. For after Arthur’s formal history, Basil continued with reminiscences of the old countryside. Of its unmetalled roads and isolated parochialism; of its bygone cottages and outside privies; of its 'straw plaiting', 'stoon picking' and 'after harvest boots', before finally showing old, black and white photo graphs of the erstwhile Suffolk-Essex border - with its narrow lanes, hedge rimmed views and shy children - posing many seconds for the camera's shutter.